F-5 LIGHTNING DEVELOPMENT

Prior to the outbreak of World War II, a few lightly modified Beechcraft C-45A/AT-7 light transport/navigational trainers were the closest thing the United States had to a combat reconnaissance aircraft. These aircraft were modified for photo work by installing a door in the starboard side of the fuselage which could be opened to accommodate large aerial cameras. Designated F-2, the combat effectiveness of these aircraft was questionable at best, suicidal at worst.

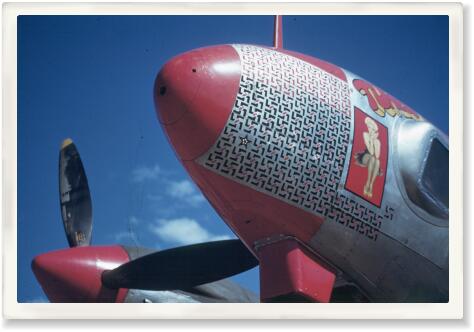

The unmistakable camera-nose of the photo Lightning. In this case it is the highly decorated veteran F-5E-2-LO (s/n 43-28332) named "Turbo Anny". Personal mount of Capt. Jim "Tut" Frakes, 332 began life it's as a Lockheed P-38J-15-LO at Burbank and was modified to the photo Lightning at the Dallas Modification Center at Love Field. (Richard Kill) With the prospect of a truly global war looming, development of a high speed photo reconnaissance aircraft was critical, and neither the Army Air Corps nor the Navy had plans for such an aircraft. At the time, the inventory of aircraft included the Republic P-43 Lancer and the Brewster F-2A Buffalo, neither of which was capable of out running or out gunning a determined enemy. The Bell P-39 and Curtiss P-40 would ultimately prove themselves in combat, but lacked sufficient range or speed to fill the need for a combat reconnaissance platform. Tests were done with a few early Douglas A-20 Havocs equipped with turbosupercharged Pratt & Whitney R-2600 engines. Although they had a top speed of 390 MPH at altitude, insurmountable problems developed in the program, and only three aircraft were converted to the F-3 configuration before America's entry into the war. The only other aircraft that seemed to meet the requirement were the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, designated F-9, and the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, designated F-7, but these were nothing more than large, slow moving targets when flying alone.

Late in 1941, Col. Ben Kelsey authorized a program to extend the range of the P-38. This decision came presumably because of the report, by Col. George W. Goddard's staff at Wright Field, pointing out the lack of a photo reconnaissance aircraft that could be flown into a combat zone. Col. Goddard had done extensive work following World War I in Aerial reconnaissance research at McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio, and was responsible for several revolutionary ideas in the field. Among his innovations were Infrared photography, long range photography, aircraft designed specifically for aerial photography as well as cameras designed specifically for these aircraft and perhaps most importantly, a long focal length lens which was later to prove its worth in World War II. The field lab for photo processing was also developed under Goddard's leadership.

To fill the need for a long range reconnaissance aircraft, Kelly Johnson's team at Lockheed produced drawings of the new P-38E Lightning fighter aircraft with all armament removed from the nose of the gondola, replaced with four K-17 cameras. Priority was given to the project and a modification center was set up in Dallas, Texas under the direction of Leo Childs. One hundred P-38E fighters were eventually diverted to the modification center and designated F-4-1-LO. In addition to the photographic modifications, major changes in the fuel transfer system and mounting shackles were made for the purpose of range extension. There were also mechanical and electrical modifications made to control camera operation and fuel management during flight. Later in the year, 20 additional F-4s came along with the designation F-4A-1-LO. In addition to the K-17 vertical cameras, the F-4A-1-LO had cameras mounted at oblique angles. The radio antenna mast had to be moved from the bottom of the nose to the top of the nose so as not to obstruct photography from the forward vertical stations.

The F-4-1-LOs flew their first combat missions with the 8th PRS in the Southwest Pacific Theater area in April of 1942. These were the first operational missions for the Lockheed P-38 Lightning of any type. F-5As were built in three production blocks. Like the F-4s before them, these were produced as purpose-built photo platforms, rather than conversions from the P-38 Fighter. Subsequent improvements of the P-38 brought new designations to the F-5. Later versions of the F-5 were modified from the P-38 Fighter either during Fighter production or in the field.

The 34th Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron primarily flew two versions of the F-5. The F-5B-1-LO and the F-5E-2-LO with lesser numbers of F-5C-1-LOs, F-5E-4-LOs and F-5F-3-LOs. The "B-model" was a purpose built airframe from Burbank whereas the later "C", "E" and "F-models" were converted from the P-38 fighter airframes either at the Dallas Modification Center at Love Field or as a field modification as in the P-38L. Camera configurations varied depending on the requirements of the mission or the weather conditions of the day. The Army's needs were for photographs of a scale of 1/10,000. To meet this need, missions were flown at an altitude of 20,000 feet using 24 inch focal length lenses, weather permitting. At an altitude of 35,000 feet, the same scale could be achieved with a 40 inch focal length lens. When the weather was uncooperative, a scale of 1/12,000 was achieved using 6 inch focal length lenses at an altitude of 6000 feet. There was also a provision to get acceptable photos below 5000 feet using 12 inch focal length lenses. Missions flown on the deck, called "dicing" missions, were employed to provide extremely urgent photos when weather did not permit vertical photography or when critical detail was needed to accomplish a given mission. The risk associated with dicing missions made them more the exception to the usual altitude of 20,000 feet.

The most widely used variant of the photo Lightning in the 34th PRS was the F-5E-2-LO. This version of the F-5 can be distinguished by these visible features numbered above: 1) gun camera port in nose; 2) teardrop shaped oblique camera fairing on either side of the nose; 3) flat (bullet-proof) windscreen; 4) 3-part air intakes under the spinners for the oil coolers and intercooler; 5) aileron trim tabs (both wings) and 6) reccessed landing/taxi light in the port wing. Given that in this picture you can see all of these features and given the tail number of 28332 (item numbered 7) -- this aircraft is clearly a converted Lockheed P-38J-15-LO Lightning or F-5E-2-LO. (Harold Vaughn) The most common camera configuration was called a "Trimetrogon" system. The Trimetrogon system consisted of a pair of K-17 oblique cameras with six inch telephoto lenses mounted in a fixed relationship to one another for a side stereo overlap of seven degrees. A K-17 vertical camera was mounted in the center section with either a twelve or fourteen inch telephoto lens and a K-18 vertical camera with a twenty-four inch telephoto lens in the rear section. Forward stereo overlap could be gained by setting the cockpit camera control. Called an "intervalometer" this control quite literally controlled the interval at which photos were taken. The cameras cycled every six seconds with the control set on "runaway." This was the maximum number of exposures that could be taken.

In high priority areas, a pilot needed to take as many photos as possible, so the runaway selection was chosen. There was also an override switch on the yoke, where the trigger for the guns would normally have been placed. This provided for a few extra shots over the target area, as well as coverage of "targets of opportunity." Care had to be taken in setting shutter speeds to ensure they were a reasonable match for the altitude or the exposures would be blurred.

The F-5E-2 was most often configured with a trimetrogon system consisting of three K-17 vertical cameras and two K-22 oblique cameras. This set up made it possible to cover an area of roughly three miles from an altitude of 10,000 feet. As the altitude increased, the coverage area would increase, but the detail of the photo would be of lesser quality. When missions were flown without oblique cameras, covers would be placed over those windows. Crews would often adorn those covers with pictures of their wives or girlfriends.

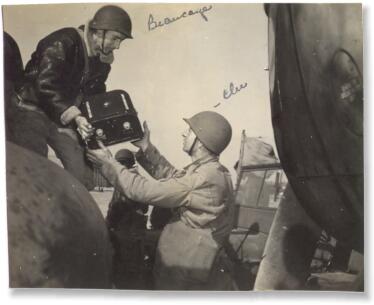

Immediately upon return from a mission, photo lab staff would meet the flight and remove the film magazines and quickly get them to the lab for processing. Seen here are photo lab staffer Raynold Beaucage and Photogrammetry (Plotting) staffer Frank Clee. (Harold Vaughn) The 34th PRS also had an F-5A-3-LO (s/n 42-12786). Aptly named "My Little De-Icer," this aircraft had been an instrument trainer prior to being refit for the low level work over what would become the American sectors of the invasion beaches of Normandy. Provisions were made for split vertical cameras and a forward facing oblique camera. A K-17 camera with a twelve inch focal length lens was placed in the nose, facing forward at a 10 degree downward angle, and two K-17 cameras with six inch focal length lenses were placed on each side. These were aimed slightly forward from right angles to the aircraft's line of flight. This configuration provided an uninterrupted coverage of more than 180 degrees. Other squadrons within the 10th Photographic Reconnaissance Group also had F-5s all specially equipped with the "dicing" camera configuration for the low level missions flown ovr the northern coast of Europe prior to the invasion.

Field modifications were quite the norm for Photo Recon Squadrons as the prosecution of the war continued and the 34th was no different. If the longer focal length vertical K-17 camera was to be carried by the F-5, a sheet metal "box" extension had to be added to accommodate the longer lens. Some sources have erroneously listed this feature as a debris guard for the camera window to keep it from getting dirty. In reality, the high tech solution to keeping the window for the lens clean on take off runs was to simply tape some paper over the glass. The wind would rip the paper off by the time the plane reached its target. This was a particularly important process at Azelot where the runways were constantly covered with mud.

Though the F-5 was heavily modified to cover a range of 2500 miles, the accepted policy called for missions from 125 to 150 miles from base. Airfield coverage was usually around 250 to 275 miles. On missions of over 275 miles, the general policy was to send fighter escort along. Practical experience showed that a single plane drew a lot less attention than a group of planes did, so most every mission was flown solo.

Since F-5 pilots flew alone and unescorted, they had to rely on the speed and maneuverability of their aircraft, their own abilities as pilots, and their wits in the event of interception by the enemy. Pilots who trained and served strictly as photo recon pilots were inclined to dive away from an aggressor, or find cover in clouds.

Pilots coming into the unit who had prior experience as fighter pilots would often turn into the enemy, forcing a confrontation. As a fighter, the P-38 had no convergence problem because all the armament was located in the nose. Most aggressor pilots knew this and would break off their attack rather than risk being shot down. Since the F-5 was a twin engined plane with counter-rotating props, it proved to be a perfectly balanced plane with no torque problems. If a dogfight situation developed, the pilot would attempt to lead the enemy to a lower altitude then bank severely to the right at tree-top level. Ultimately, during the pursuit of the F-5, the torque from the single engine of the aggressor plane would force it to snap-roll into the ground, eliminating the problem for the photo pilot.

Photo reconnaissance missions were often more important, as well as more productive, than bombing missions. This is because allied commanders needed to know target locations and the defensive capabilities thereof. Once the target was hit, bomb damage assessment was necessary to determine if the target had been destroyed or if further action was called for. Here's the thoughts of 34th PRS replacement pilot Col. Charles "Charlie" Hoy (USAF-Ret.)...

"We never knew why we were drafted out of fighters into photo.

Actually, with a promise that we'd get back into fighters soon!

But we never looked back. Seeing our mission as "Photo Joes"

got in your blood quickly when you understood the mission and

could visualize the results. I'd honestly never even heard of

photo reconnaissance...much less expected to enter the war as

a singleton. I thought I'd be a wing man for someone for a

while. To suddenly be the navigator, the photo operator

and alone...was mind boggling.

Donn [Hayes] had me go to the photo lab after my first mission

and follow my film. I'd never seen a photo lab. But there was

an Army BG [Brigadier Genenal] and British Air Vice Marshall

looking at the wet negatives, then laying on missions from a

field telephone! Wow!" -Col. Charlie Hoy (USAF-Ret.)Due to the success of the P-38 as a pure fighter, its success as a photo surveillance platform has been largely overlooked. With range extension modifications allowing for a set of 300 gallon drop tanks, the P-38/F-5 had a range of about 2500 miles. Top speeds varied from 395 MPH at 25,000 feet to 430 MPH 30,000 feet. Dive brakes and aileron boost were added to the design of later models of the "J" family, adding to its handling characteristics. In short, the performance of Lockheed's Lightning allowed unarmed photo recon pilots to get out of trouble faster than they could get into it.

Sadly, with the end of the war, the F-5s were deemed too expensive and too difficult to maintain to keep in the inventory. The F-6, considered to be more economical to operate in a post-war era and easier to maintain, would be its successor.

Designed to fill the need for a tactical "on-the-spot" recon ship, the F-6 (based upon the North American P-51 Mustang) would soldier on to do the "Casey Jones" photo-mapping of most of what would become the Warsaw Pact and newly expanded Soviet Union. In the end, all of the squadron's F-5s were wired with primacord around their tail booms and were destroyed.