Part VI

With the coming and going of Invasion Day the 34th had covered quite a spectrum of mission profiles. To mention just a few we had crossed the channel at wave-top level actually churning up spray with our props to hit our targets "on the deck" at times we had covered the so-called dangerous medium altitudes; and of course, we had reached out into the higher heavens to 30,000 feet and above in performing all of our earliest missions. Our aircraft was the "best". For our purpose, in its day, it met our every requirement. Even at the extreme altitudes when cracked magnetos and associated engine failure sometimes seemed more than common we always had the second engine to bring us home. Our "F-5s" under all conditions really "brought home the bacon".

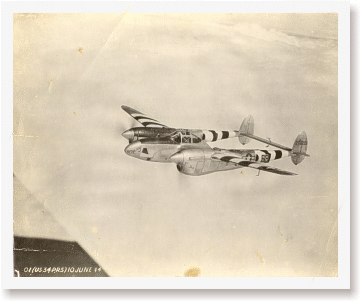

10-June 1944 - F-5B-1-LO "Mary", (s/n 42-68229), is caught on film over the English countryside just after D-Day (wing of chase plane in lower left corner of picture). It's interesting to note that Monogram produced a quarter scale P-38 Lightning plastic model which included a F-5B conversion and decals for this aircraft! Widely distributed, the model and the photo, are well know in the community. (Rhymer Myers) In the few months of operational flying just passed we had learned much and several of our original tactics had gone through many changes since flying our first missions. But our mission change to lower altitudes was undoubtedly the most significant ramification.

Four of our original eighteen pilots were all lost while we were flying missions at the extreme altitudes of 30,000 feet and above. The losses of Lieutenants Cameron, Sizemore and Knickerbocker were all attributed to "anoxia" (loss of oxygen) and although Lt Lloyd Haslup was listed solely as "Missing in Action" we always felt that his loss too could have been indirectly associated to oxygen failure. In other words failure and/or inadequacy of our early life-giving support systems at extreme altitudes were more than likely the cause of our early pilot attrition -- not necessarily enemy action. Later on the continent, we lost three more pilots, Lieutenants "Skip" Walters and McKee at Dijon and Loyal Herndon at Azelot/Lupecourt. None of these losses were attributed to "anoxia". However, Lieutenants McKee and Herndon were our second and third pilots to be listed as Missing in Action. (At most, then, we attributed but three losses possible to enemy action.) The following accounting of this squadron anoxia near-mishap brought vividly home the dangers so closely associated with high altitude flying in the "Wartime '40s".

Fortunately in this instance, Lieutenants Bosworth and York were flying across the channel in a two-ship formation before separating at the French coast to go on to each's own target area. Upon reaching 30,000 feet over the channel Bosworth noticed that York, flying on his right wing, was flying quite erratically and when contacted by radio he also responded somewhat incoherently. Alert to the "anoxia" problem "Bos" immediately flew downward to a lower and less critical altitude "talking" Garland safely along with him. Although more responsive at the lower altitude York's communication contact continued to be somewhat vague and even erroneous--on two altitude checks reporting a 10,000 foot reading higher than their actual flying altitude. (Actually, Garland was only several hundred feet above the water at the time.) Bosworth immediately escorted York "up and away" to the nearest RAF Air/Sea rescue base where he landed safely. Even though given a rather hasty physical exam by the RAF Flight Surgeon and pronounced fit to fly his plane to his home base, (some two or three hours later) Lt York fainted while deplaning at Chalgrove. He was immediately grounded and remained under close medical attention for several days before returning to his normal flying duties. This was a most vivid recollection of the seriousness of anoxia effects fortunately brought home this time to be talked about.

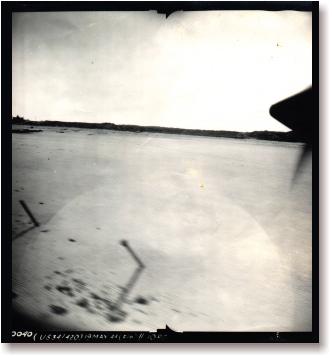

As we dropped down in altitude our serious oxygen problems diminished. This was particularly apparent when we commenced flying most of our Third Army support missions at 20,000 feet. Not only did this altitude provide almost ideal scale photography for our users it also proved safer and more comfortable for our pilots. Oxygen usage, of course, remained a necessity but our margin for error was not critical as it had been at the outer limits. The lower altitudes did prove a blessing in disguise. Even so, however, at the other end of the spectrum was the low-level "dicing" mission--and here, too, there were limitations. We always felt that there was a time and a place for the "on-the-deck" mission-- the invasion Beach Photography was one of few positive examples. Low-level photography was unquestionably very spectacular; it had the "Hollywood flavor"--it certainly made for good "publicity stills". But from a truly operational point of view, more than often, it was "overplayed". In actuality it was relatively poor "scale" photography; it was distorted; and, surprisingly, it left much to be desired from an 'interpretation' standpoint. In almost every instance our consumers preferred an "end-product" of vertical photography taken at 20,000 feet. Other than the occasional exception, from here on out, we "shot 'em" all at 20,000 feet whenever possible.

19-May 1944 - "Dicing" mission photo of what was to become Omaha Beach - Normandy. This shot is representative of the distortion common to these zero altitude sorties. This shot, taken by Lt. Garland York in the squadron's F-4A "My Lil' De-Icer" by the starboard oblique camera, shows beach obstacles in the form of posts with anti-tank Teller mines straped to the tops. Note blur atop bottom center post is a mine. Starboard propeller spinner is in center right of image area. (Ray Lanterman via Charlie Lanterman) Another operational tactic practiced from the outset by the 34th was that of flying our missions alone and completely unescorted. This was a tactic which we did not change.

Single unarmed "Photo Joes" were always ballyhood as the "lone wolves of the skies". This was basically true, however, as the war progressed and the targets became more critical and dangerous to get to, fighter cover was often requested to escort the photo plane in to and away from the target area. From the first the 34th, with but one or two exceptions, flew its missions alone with no escorts. The pilot depended on speed, evasive action and generally altitude for protection. We had strong convictions that one aircraft flying rapidly over its target attracted far less enemy attention.

Even though the question of Air Superiority remained a moot question until after the invasion the unarmed photo pilot never wasted much time figuring out who might be in the position of superiority--he knew only too well. In addition, the 34th pilots strongly felt that the Third Reich was concentrating its strength and resources more against massive allied air attacks than against the solitary "Photo Joe" sortie. From both intelligence reports and our own enemy exposure it was readily apparent that the German Air Force and Air Defenses were becoming more and more economy-conscious on its usage of aviation fuels, ammunitions and other critical items. This was emphatically recognized not only when our sister squadrons but when, in particular, the photo squadrons based in Italy and flying missions north in our area asked for and got fighter cover on some of their photo sorties over the well known "hot spots". In every instance the increased air activity on their part generated an equivalent amount or more of enemy activity. Only too frequently this action resulted in mission failure due to loss of photo plane and pilot; and more than often the 34th would hit the same and/or similar "trouble spots" alone with one ship and experience little or no enemy retaliation.

Although it would have been comforting a time or two to have had a few armed chums along we pretty well stayed with the single-ship concept. One exception shortly after the Invasion again served to prove our point. If memory serves me correctly, we launched a ten or 12-ship mapping mission in support of George Patton over the Brest Peninsula. As could be expected our simultaneous arrival with that number of planes over the target area immediately stirred up a hornet's nest including one helluva lot of "flak". Fortunately this time we all returned with our photography and skins. During the next few days, however, several single missions over the same area including the heavily defended St. Nazaire sub-pen area were flown with little or no "flak" tossed our way. This was very typical of the times and the single ship concept proved quite successful for the 34th.