Part VIII

At Chateaudun, once again, the squadron was told to set up temporarily as another base forward was contemplated. Temporary was a modest description. Actually, the field and the surrounding area was a mess -- everything -- aircraft, hangars, buildings were all in ruin; and bombs and ammunition were lying about all over the place. It was almost impossible to even put your pup tent in place without putting it on something explosive in nature.

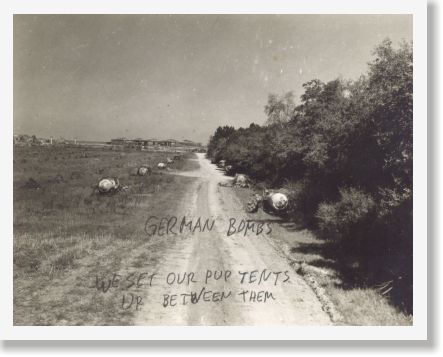

Rows of German SC 1000 "Herrmann" bombs line a dirt perimeter road, abandoned at Chateaudun by the retreating Luftwaffe. Weighing in at 1,000 kg (2,205 lbs.) the SC 1000 was one of the larger freefall weapons carried by the Luftwaffe. Handwritten notes on the photo read, "German bombs", "We set our pup tents up between them." (Lou Cerino) The Germans had had big plans for Chateaudun. Purportedly, it was going to be the "jumping-off place" for bombing not only London but one-way missions to New York City as well. Huge multi-section "casement bombs" to accomplish this were scattered about the area.

And it was here that we lost our "Charlie" -- almost forever. While "sweeping" his living area of scattered ammo (the Lanterman family seemed to have a "thing" about "clearing the way") Charlie became entangled with a "hot" HE shell. The end result: a shed full of smokeless powder; Frank Dehoney, our squadron intelligence officer, suffering from an unexpected shave and haircut; and Charlie Lanterman in a dazed prone position minus a few vital body parts. Charlie, fortunately, recovered and returned New Year's Day 1945 -- minus an eye and a couple of digits -- to do an outstanding job for both the 34th and the 10th "Reece" Group. Quite a guy.

While the squadron was at Chateaudun the capture of Paris was taking place; the British had crossed the Seine; and the Third Army had passed St. Dizier and was gobbling up territory all along the Mozelle including Nancy, France. General Patch and his Seventh Army was coming fast from southern France and pushing lots of Germans ahead of him. It was at this time that the Third Army's "right flank" appeared most vulnerable. When asked about his open "right flank", General Patton replied that the XIXth Tactical Air Command would provide his "right flank". And it did.

It was also here, at this time, that our on-the-spot visual reconnaissance picked up a rapidly retreating German division on the move north towards the Loire from Chateauroux. At one time leading elements of this outfit were momentarily breathing down our necks on our side of the Loire a mere 25 miles from our pup tents. Fortunately, they were more interested in "surrender" than "attack". As it turned out "Opie" Weyland, our Commanding General of XIXth TAC provided an American Air General Officer at the appropriate place and time on the Loire River bank and almost an entire German division -- officers, men and equipment -- surrendered to the Army Air Corps without a shot being fired. I guess George Patton knew what he was talking about -- XIXth TAC was watching his "right flank". It did happen.

Since the breakout following the invasion the rapid advancement of the war had called for more on-the-spot reconnaissance than photo reconnaissance. But by the end of August the Third Army was forced to halt its great advance just east of St. Dizier because of the long supply lines that the rapid advance had created. In effect, the allies had created a "monster" and it would live to "sting" us before it was all over. The delay gave the enemy what they needed most -- the opportunity to "dig in". They did, all along the Mozelle River from south of Nancy to Trier in the north. The long defensive of the winter had begun and with it, once again, came the ever-increasing demand for photographic reconnaissance and plenty of it.

To meet this demand the 34th again changed bases, moving to A-64, St. Dizier, France 12 September 1944. But this time the squadron was told to set up as permanently as possible. It looked as if we might be around for awhile.

At the time, St. Dizier was the most advanced air base on the continent. Because of the confusion it was a veritable "O'Hare International". Dispersal of aircraft was almost unthinkable. The "St. Dee" airlift was in full swing. C-47s came in day and night parking nose to tail while they off-loaded fuel in containers of all sizes down to and including five-gallon "Jerry" cans of gasoline to awaiting six by sixes who in turn were "Red-balling" it forward to Third Army tanks and other armor. To add to the problem a couple of our "heavies" from England, looking for a safe haven to land, had crash-landed; and the aircraft from the famous 354th Fighter Group were on hand and temporarily operating from "St. D" flying cover for the operation -- confusion and all.

Hopefully, we had achieved air superiority -- we'd better had, even one misplaced bomb and the whole place would have "gone up". Believe me, "Big D" was a whirl of activity and it was amidst this setting that our advanced air echelon made its appearance.

Actually, this move probably gave the squadron more headaches than any other as it came right in the midst of the heaviest load of missions since operations began. In fact, our advanced air detail -- tool boxes in hand--deplaned their C-47 one hour and fifteen minutes after takeoff from Chateaudun; just a short time later they were madly servicing our aircraft which had already completed first missions of the day after taking-off earlier from Chateaudun. Several more were flown that late afternoon before a mighty "dead" bunch of mechanics and refueling operators spread out on the runway concrete for a quick "five". It was only a couple of days later that the 34th broke its own record of missions flown in one day, "29" -- and this was to be broken several times again before the end.

A pair of venerable Douglas C-47s is the subject of another of the spectacular color slides taken by Richard Kill with his Polaroid camera on ASA-12 color-slide film. Rich kept snapping pictures until Col. Hayes caught wind of his photo record and asked that he "knock it off." (Richard Kill) There was no question the fighting in France had accelerated -- and was more static in nature. We performed around-the-clock with little rest. During the period 10-13 September approximately 10,000 square miles of territory was mapped by the 31st and 34th Photo Squadrons of the 10th Group. And the following week over 200,000 prints were delivered to the Third Army. Believe me, photo lab, plotting and interpretation personnel aren't exactly "basking in the sun" during this kind of heat.

On our Chateaudun/St. Dizier move I had fronted our main convoy body to monitor a bit of our ground operations. I quickly found out. More than a few hours of that trip took place during darkness. I'll tell you, you haven't really lived (maybe never again) until you have traveled the French war-torn biways by convoy under rigid blackout conditions (remember those little "slits" called jeep headlights) with tough Third Army MPs and their "Thompson subs" prodding your "butts" at 35-45 mph plus speeds. I sure made a quick mental note to keep my nose in the "air" from there on out and leave the driving to "those who knows".

To Dick Wiltse and his advanced detail went the plaudits on this move. He was moving his "stream- lines" group of operational personnel and equipment to get things going at the new base. Just outside "St. D" he was stopped by the Third Army MPs at a large German Depot. Third Army, of course, had liberated it. Stocked with "liquid refreshments" of all types and brands, General Patton had personally issued orders reserving a large share for the Air Corps -- included, of course, were our units moving forward to St. Dizier. With dispatch, Major Wiltse proved up to the task at hand. He off-loaded his "top priority" operational equipment and in turn on-loaded his new "red-ribbon" manifest and high-balled it for a quick but necessary stop at our new living area at St. Dizier -- after all, "damn the shipping crates et cetera..." A couple of days later each man in the squadron received a 5-star bottle of Hennessey Cognac and subsequently, additional treasures from the coup from time to time -- all, of curse, with the personal compliments of General Patton. C'est la guerre.

"Put my nose back in the air", I did--right away but almost once too often. We were now flying missions well into Germany's homeland. 29 September I flew a mission from St. Dizier northeast passed Trier to map an important but relatively small area on the Lahn River near Limburg -- my primary target. My secondary targets included airfields and two ammo dumps further into the "hinterland" in the Koblenz/Giessen/Wiesbaden/Frankfurt areas. It was a good mission accomplished with all targets photographed successfully. It was a clear day and the skies were full of activity -- both ours and theirs. Fortunately, I had run into no trouble -- even over the heavily-defended Wiesbaden/Frankfurt area. However, a single enemy aircraft near Trier on my way home suddenly changed all that.

September, 1944 - Taken in France, this is Larry Schmidt's F-5E. Note on back of photo reads, "Not having a wife or a girlfriend, I told the mechanics to put anything they wanted to on it. They came up with the name "Strato-Snob" and the cute cartoon character." (Larry Schmidt) On my way home -- mission already accomplished, I thought -- I was actually almost day-dreaming; I had even started (somewhat pre-maturely) a gradual let-down before passing into friendly territory. Suddenly, at a phenomenal rate of speed, a short stubby aircraft shot immediately in front of me in an almost vertical ascent. The aircraft and its contrail rapidly disappeared above me into the sun. No armament was observed; nor were shots or tracers seen -- just speed and plenty of it. This was definitely not one of the Luftwaffe's new operational ME 262 jet aircraft. I did observe, however, a burst of flame from its tail assembly as it made its "intercept" and rapidly passed me on into the heavens. Shocked out of my doldrums need I say I did a "split S" for the "deck" and streaked for home and safety. I was one perspiring lad when I left the cockpit that day. I had tentatively identified the aircraft as a ME 163.

After scouring all our intelligence sources, upon my return, I positively reaffirmed the intercept as a ME 163 aircraft, Rocket Ship--the "Comet". (A German interceptor powered with a rocket engine. Although approximately 370 saw service and several actually became operational it really never reached the "true" operational stage as did the ME 262 jet. At full power it presumably had, at most, a 10-minute flight duration. It took off from a wheeled platform which was jettisoned from the aircraft at lift-off to later land on "belly skids" presumably at its point of take-off). A complete "flash report" of this mission was filed immediately with 9th Air Force, and it was later confirmed that both R & D and some operational aircraft of this type had been observed in the Wiesbaden/Trier area. On reflection I have always felt that this particular incident was a "test-intercept" by the Germans after tracking my flight path from Wiesbaden home. Test or otherwise it sure scared the devil out of this lad -- that September day in 1944.

Messerschmitt Me 163 B-1 Komet

First operational mission for the Me 163 Komet, an unsuccessful interception of a pair of P-47 Thunderbolts, was flown by Major Wolfgang Sp�te on 14-May 1944 near it's Bad Zwischnenahn test field. First combat mission of the Me 163 was the unsuccessful interception of a photo Lightning on 7-July 1944, flown by Unteroffizier Konrad Schiebeler of I./JG 400. (Tom Tullis)It was just a few days later that Bob Holbury of our sister squadron, also penetrating German territory, was intercepted by one of Germany's more sophisticated aircraft -- this time an ME 262 jet. Just in a matter of a few days two photo "recce" pilots were "privileged" to a "pre-showing" of modern day aircraft -- a preview of things to come. To our best knowledge these were the first reconnaissance pilot contacts ever with enemy rocket and/or jet aircraft. It did happen.