Part X

It was on our move to Dijon that we experienced our first enlisted fatality of the war. To avoid hitting a Frenchman and his bicycle who darted out of the woods on a narrow bi-way into our convoy, Alfred Melchionna, of the transportation section, swerved and lost control of his vehicle at the last minute hitting a tree along side the road. It was a desperate but heroic effort on Melchionna's part which cost his life.

The First Tactical Air Force (Provisional) had just been organized to support the Seventh Army as well as the French First Army coming up from southern France. The demand for air reconnaissance was A-1 priority for General Patch as it had been for Patton. And to meet this demand the Provisional Reconnaissance Group (XIIth TAC) was formed at Dijon with the 111th and the 162nd Tactical "Recce" Squadrons providing the on-the-spot visual reconnaissance and the 34th handling the total photo effort. The 13th photo detachment was attached to give a hand in photo reproduction. Also, the First French Photo squadron, although not officially assigned, latched on to our coattails for a short period to join in. (I don't ever remember that the French squadron ever boke any operational records but their cuisine was sure something to write home about -- they gave us a good sample at Dijon to welcome us all-aboard).

The 111th was a truly battle-seasoned squadron. It had learned it's lessons the hard way in North Africa and applied them well in the Sicily and Italy campaigns on its way northward. Now under the leadership of Major Luther Randerson they were a real bunch of "pros" -- probably the most experienced "TAC R" squadron in the ETO. The 162nd was a relatively new arrival from the Zone of Interior but moving right along. You know what the 34th could do. But the 13th Photo detachment was a pretty well worn-out "Blue Train" picked up in Italy to provide the mass photo multi-printing reproduction effort for the Group. Through 34th ingenuity this unit would be resurrected practically from top to bottom during the next few weeks. Photo lab, transportation and engineering personnel teamed together to really do an "innovative job" on this "baby".

And speaking of French cuisine, I believe since our arrival on the continent and at least by the time we had left Dijon -- that each man in the squadron had finally had the opportunity to savor the hospitality of a French family or two in their home -- their food, their wine, and of course, their "Calvados". The French, all in one manner or another, were eager to express their appreciation and gratitude for the arrival of the Americans in France -- Vive L'Amerique". After witnessing our endless chain of armor, trucks, heavy engineering and other earth-moving equipment roll over their road network they now understood, at least in part, why the invasion had taken so long in coming. (And, Charles Scobey, included in that endless chain was at least one six by six loaded with bicycles -- the engineering section. I now know of at least one of those bikes that was sold for 1000 francs. And I have a sneaking hunch, if the truth were known, another truck or two undoubtedly found their way similarly to the continent. C'est la guerre).

Along with the weather I started complaining about it right away -- right to our Group Commander. (Of course, I knew better -- after all as the saying goes, "when you 'bitch' about the chow you somehow always wind-up being the mess officer"). True to form, I had just acquired another "extra duty" -- this time, "keeper of the strip" and "on your head be it, Donn". (Gee, thanks, boss -- I hope you just happen to have that Aviation Engineer Battalion in your hip pocket). So I moved to the strip -- and believe me, I joined up with a bunch of great guys when I did.

Actually, we had requested engineering support immediately when we first saw the Azelot site and the urgency of the situation fortunately expedited its arrival. Just in time the engineers thundered in, heavy equipment and all -- God bless them. The Engineer Battalion was an all-black unit -- every man from the South, no doubt, and I don't think any of them had ever seen a white snowflake before. Down to the last man they knew their job and they really did it. Theirs, was a tremendous effort.

During the next three months our strip was actually rebuilt three complete times with one helluva lot of "major mending" going on in between. First, it was "Hessian Mat" and heavy wire mesh over the entire strip -- it helped but we continued to sink. The "Pierce Steel Plank Stage" followed. In addition to "PSP" this included more matting, wire mesh and a lot of gravel here and there in the really bad spots, and there were plenty. We found ourselves still sinking and the buckling of planking made for potentially hazardous conditions for landing gears and tires -- particularly our F-5 nose wheels.

Finally, it had to be done--the touchdown areas at each end of the runway had to be completely rebuilt and reinforced -- this actually represented about two thirds of the strip. Up to eighteen inches of gravel all trucked from the Mozelle River bottom was laid. This was topped with more Hessian Matting and wire mesh. Under the conditions it was an almost impossible task.

Necessity demanded that much of this effort be done at night; it was all done under the worst of conditions; and it was all accomplished without even a minutes loss of combat mission flying time. (During this period we did have to close the strip down for about two hours one afternoon due to an emergency B-24 landing which damaged a section of strip, but the engineers took care of that too). An equally important encore performance, both quickly and professionally, on our taxiways and hardstands; plus several subsequent "curtain calls" all necessary and the engineers had finished their job. That winter we had all, truly, witnessed an engineering miracle.

One of the many "visitors" that winter of 1944/45 at Azelot. (Richard Kill) But the engineers weren't the only heros at Azelot that winter. Conditions on our taxiways and hardstands were just as bad and perhaps more critical there to our over-all operation than on our runway. After all, it was there where our communicators, camera repairmen, refuelers and mechanics were working their hearts out to keep 'em flying. The hardstands when not resembling the "La Brea Tarpits" were frozen over -- hardly an "Air Depot setting" for our line personnel. In fact it was miserable -- a living hell.

On the shoulders of Jim Frakes, the squadron's new operations officer, went the job of ramrodding and synchronizing the total operation effort of the 34th. He had his hands full. But I assure you, "Tut" was more than equal to the task. He also moved into the "Pits" -- living around the clock on the strip in order to quarterback the tremendous team effort required to keep it all going on the line. It had to be done.

When not in mud "up to our ears" the workers on the line were literally freezing. With temperatures hovering around zero engine changes, major repairs and even some depot maintenance were made in the worst of conditions -- mechanics hands actually stuck to the cold metal at times. When conditions were at their worst our men had to relieve one another every fifteen or twenty minutes in order to keep from freezing fingers and other vital extremities. I think Charlie Hoy, in recent written comment expressed it best when he stated..."even new furlined combat jackets and gloves couldn't always keep a man warm on a ladder trying to repair a fuel line at 0 degrees in a 30 knot wind. It took a lot more than technical ability to keep 'em flyin' that winter."

The ruggedness of Azelot/Lupecourt didn't end on the line. The severe wintry conditions made its presence felt everywhere and on everyone -- but no one said "uncle". Time and time again we ran out of coal - - but we got it; slabs from a nearby sawmill were at a premium--but we got them; scrap lumber for fire wood, at any price, was in demand--but we found it; to say the least, it was difficult to get the materials to winterize our tents -- but we finally did it. It was in this environment that the "Back-up Gang" -- the "Unsung Bunch" -- performed its best.

Supply flow, at times, reached critical stages but the Thirty Fourth always managed; airplane and camera parts in "short supply" were "jerry-rigged" and/or rebuilt to keep the aircraft airborne; and it was during this period that squadron team effort rejuvenated the photo reproduction unit; we even "stole" a B-25 plane load of photo multi-printing paper in Naples, Italy to tide us over during a most critical shortage in December. (There still might be some court-martial papers floating around somewhere in Italy because of this little stunt--this one with my name on it).

Yes, tempers were raw; men were on edge; and the tension in the air was taut--even so the squadron continued to perform both professionally and effectively. The work of the "Back-up Gang" was an important contribution to the total effort that really put it all together -- and all of this was truly the "Back-up Gang" in action. It was voluntary effort; it was done because it had to be done; there wasn't a contingency plan for this brand of effort and you won't find it documented in the "book". It was just total team effort, the end result of honest desire to get the job done and effected by the unsung heros of the Thirty Fourth.

The "Unsung Bunch" was always a busy band. They manned special details such as washing down F-5 landing gears from mud (picked up while taxiing to take-off position) just before takeoff to prevent gear retraction and extension malfunctions; and they doubled up on guard details so mechanics and others could work round-the-clock on their aircraft; with no questions asked, unrationed steaks, fresh eggs and even a stray goose or two appeared on the menu -- thanks to Hank Fregulia and "friends" in this instance; and, I guess our "scroungers", "moonlighters" and "midnight requisitioners" put a lot of it together with a well-placed package of cigarettes and a few chocolate bars. Really now, who in the 34th could say he didn't play a part in this effort. It was "total" -- total effort that did the job for the 34th.

Gentlemen, believe me, there was suffering and pathos aplenty, but I assure you, there was a lot of "greatness" on display at Azelot/Lupecourt during the winter of 1944/1945.

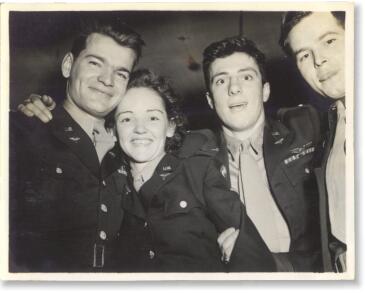

A bigtime on the Ole Town tonight! 34th pilots Wallace Bosworth, Larry Schmidt and Jim Lively enjoying the goodtimes, and plenty of spirits for sure! Larry Schmidt had this to say about that memorable evening. (Charlie Hoy)

"I remember that situation quite well. It was taken at a party that the Officers Club laid on in St Nicholas, the field near Nancy. It was a fairly wild one as I remember. I know I was dead drunk at the time, and I know Jim lively was too. I don't know about Bos. Bosworth is on the left, the nurse was from a nearby hospital unit, then me and Jim is on the right. It was in late November, because I remember it was very cold for that time of year. One thing I might know is that the lady was partial to Bosworth. I might mention that at every dance or shindig we threw, the married men got all the women. I don't know if it their experience with women or the shyness of us young bachelors. We had some good parties before, but this one was one of the standout ones."There were moments, too, in which we could mix the sweet with the bitter. With the weather at its worst, particularly November and December, it was usually bad everywhere and more than often all aircraft were grounded. In one way these were welcomed days for it provided all sections some extra time to catch up on their backlogs at a somewhat more leisurely pace -- engineering and the photo lab particularly.

Thanksgiving, itself was a "Great Day'. It turned out to be a day of rest, and much deserved. Not a plane was able to get off the ground. But Hank Fregulia and his "friends" really took to the "Blue". It was a Thanksgiving feast with all the trimmings; too, several unrationed containers of "liquid refreshments" made an unexpected appearance. As far as the squadron was concerned this one would have put the "Waldorf" to shame. And "I know not from where the rations came" but for several days thereafter choice delicacies continued to flow our way.

Nancy, too, on occasion, served to brighten our day. One of the larger cities in Alsace Lorraine, reasonably near our base at Azelot, Nancy attracted us all. A great American Red Cross Club with all the amenities was a good start -- Oh, those hot running showers, how sweet they were. The first big squadron party since our arrival on the continent was a successful sequel. And, of course, the opportunity to just sit down and talk with real "All-American" nurses provided some mighty refreshing moments. The Army General Hospitals located there, the frequency of U.S. hospital trains operating in and out of Nancy, and the Evacuation Hospitals near the front but quite accessible to Nancy provided us with this much forgotten luxury. (Less we forget, the 34th was not the only ones burning the midnite oil -- the nurses from the "Evac" hospital surgical teams, if at all possible, were truly putting in 36 hours out of every 24 at the operating tables. They were actually dead on their feet -- totally "bushed". Believe me, they too were a dedicated bunch -- I know, I married one a bit later on).